Communities considering relocation from flooding often use a tool called cost-benefit analysis. But there may be better ways they can weigh their options.

by Ben Cross, Vanessa Lueck & Brent Doberstein

Coastal and inland flooding are becoming increasingly frequent and severe across Canada and British Columbia, as seen with the 2021 atmospheric rivers in lower B.C. and the 2024 flash flooding in Toronto. Various adaptation strategies can help reduce the risks associated with these events, one of which is managed retreat—also referred to as managed realignment, planned relocation and other similar terms.

Managed retreat involves strategically relocating people and structures out of harm’s way. The design and execution of managed retreat strategies have far-reaching implications for policy, practice, and community wellbeing. Decisions on managed retreat can significantly impact short- and long-term costs for communities and people, along with quality of life, environmental health, and social equity.

Community-led managed retreat (CLMR) builds on this concept by emphasizing the active involvement of the community in planning and decision-making. For CLMR to succeed, strong community support and thoughtful decision-making are crucial. As flooding risks rise with climate change, CLMR is emerging as a vital strategy for effective and equitable adaptation.

A recent report by the PICS-funded project Living With Water sheds light on the complex considerations surrounding managed retreat. The report, Economic Assessment and Decision-Making for Community-Led Managed Retreat in British Columbia, particularly examines the role of cost-benefit analysis (CBA).

The Cost of Cost-Benefit Analysis

While CBA is a widely accepted method for comparing available options, it has limitations, especially in capturing intangible environmental, social, and cultural costs and benefits.

Cost-benefit analysis measures everything in dollars. However, it is often difficult or impossible to monetize some of the costs of retreating from areas of present and future flooding, as well as the benefits.

- For example, moving away from a flood area could mean losing connections to place and community.

- In 2022, the municipality of Grand Forks, B.C., bought and began demolishing about 90 homes in North Ruckle, the area most at risk of recurrent flooding. Soon, the neighbourhood will no longer exist.

- As Jason Thistlethwaite, a professor at the University of Waterloo’s school of environment, enterprise and development, notes to the CBC: “You may be asking people who’ve lived in the community for generations if they want to leave. You may be asking people who can’t afford to take the buyout and then move somewhere where the housing is more expensive.”

- In these circumstances, making space for residents to grieve and to remember can be important. A good example is the work of North Ruckle resident Les Johnson, who decided “to capture North Ruckle before it goes away completely and present that, along with the history, in a way that makes it accessible to everyone, at any time, on the web.”

- Conversely, there are benefits that cannot be monetized, such as an improved sense of safety. Living in a home that has flooded multiple times before can cause stress, worry, and affect someone’s mental health. Removing the worry of a flood from a municipality, and restoring the land to nature, can benefit the entire community as well.

- In High Level, Alberta, after its massive 2013 flood, the city bought out two neighbourhoods which were then turned into green space. Craig Snodgrass, High Level’s mayor, told The Globe and Mail in 2022: “Now there are walking paths, mountain bikers, people walking their dogs — it’s just a nature area, it’s a great massive addition to our greenspace.”

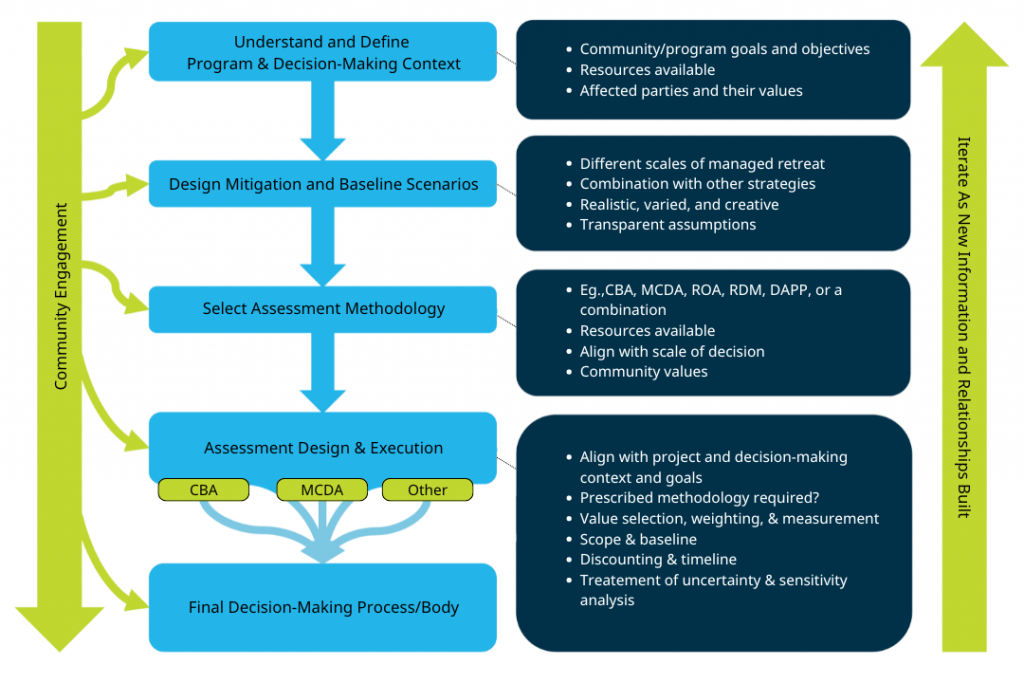

Taking these limitations of CBA into account, the Living With Water report advocates for a more holistic approach to decision-making, integrating tools like multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), which compares proposed options across a range of quantitative and qualitative factors, to account for non-monetary factors, alongside CBA. This combination can provide a more comprehensive understanding of trade-offs and encourage informed community discussions and engagement.

Improved application, better outcomes

Credit: iStock

While CBA will continue to influence managed retreat decisions, improving its application can lead to better outcomes. MCDA, when implemented collaboratively, can ensure that diverse community values are considered.

However, MCDA’s collaborative approach can be time-consuming and expensive, and choosing the best form of MCDA can be challenging. Assigning values and weights is open to bias and manipulation by influential groups, and some values may still be difficult to score or involve sensitive information.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to managed retreat assessment and decision-making. However, certain general recommendations and key principles can guide the design and implementation of an effective decision-making process for managed retreat.

- Context-specific: Tailor the assessment and decision-making process to the specific situation and needs of the community. What works for one group or purpose may not fit another.

- Community-driven: Involve the community as much as possible in every stage of planning and decision-making for managed retreat.

- Process over outcome: Focus on creating a strong, valuable process for assessments like CBA and MCDA, as the process itself can be more important than the final outcome. A strong process can build trust and lead to more collaborative, long-term relationships between all involved.

- Creative and community-driven scenarios: Encourage diverse and creative solutions that reflect community values and address broader societal goals.

- Center community values and equity: Base decisions on community values and strive for fairness. Especially consider how risks and solutions affect people who are poor, racialized, disabled, colonized and/or otherwise marginalized. Engage groups and communities of these affected people as part of decision-making.

- Understand and address uncertainty: Identify and manage uncertainties in assessments, such as the rate of climate change, changing costs, where future development occurs, or the development of new technologies. Test how changes in parameters might affect outcomes.

- Consider multiple tools, approaches, and inputs: Combine cost-benefit analysis with other tools and methods, like MCDA, to get a comprehensive view of options.

- Understand limitations: Be aware of the assumptions, uncertainties, and limitations of assessments when interpreting results and making decisions. Some examples include the price assigned in an analysis to non-monetary values; data limitations; and missing values and viewpoints.

- Proactive planning: Try to do as much planning and community engagement as possible before a flood happens, even if full retreat isn’t yet feasible.

- Learning and adapting: Make sure the decision-making process includes opportunities for learning and adjusting for everyone involved in the process as new information and relationships develop.

As flooding and other climate-related hazards become more frequent and severe, managed retreat will play an increasingly important role in long-term adaptation strategies. The Living With Water report emphasizes the need for robust decision-making processes that reflect the needs and values of affected communities. Establishing such processes sets a strong precedent for future planning and funding of managed retreat, along with broader climate change adaptation efforts.

The value of involving the community at every stage cannot be overstated. Tools and approaches should be tailored to the specific community and decision-making context, empowering the community to take charge of its own future.

Engaging the community throughout the decision-making process is not just a suggestion but a necessity. It’s a way to ensure that the maximum benefits of managed retreat are realized and that the process truly reflects the community’s needs and values.

The full Living With Water report expands on the 10 key principles for managed retreat assessment and decision-making, and provides an extensive list of sources and case studies to guide communities in making better decisions. You can also read the two-page brief that summarizes the main points, including on CBA and MCDA, case studies, lessons and good practices, and challenges for future projects.

Ben Cross is a research assistant with the Living With Water project, and a PhD student at the University of Waterloo with the Waterloo Climate Institute.

Dr. Vanessa Lueck is researcher-in-residence, coastal adaptation, with the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions, and is a principal investigator with the Living With Water project.

Dr. Brent Doberstein is an associate professor at University of Waterloo in Geography and Environmental Management.