Climate change demands action, and researchers from across disciplines are responding. But what if the solutions they develop, like technologies to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, raise public concerns?

How people perceive climate mitigations at meaningful scale is key. How do people think about some of the new technologies that might be used to address climate change? What attributes might influence broad social, scientific and government support?

Scholars in the social science arm of the Solid Carbon project are researching people’s responses to negative emissions technologies (NETs), which are approaches to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. And they’ve found that one factor might be how urgent and severe they feel the climate crisis is.

Solid Carbon is an international research project led by Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), a University of Victoria initiative, and funded by a PICS Theme Partnership grant.

Dr. Terre Satterfield, Professor of Culture, Risk and the Environment with UBC’s Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES), co-authored two papers with Dr. Sara Nawaz, Director of Research at the Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy at American University, who contributed to this work as a postdoctoral fellow at UBC/IRES, and former UBC/IRES postdoctoral fellow Dr. Guillaume Peterson-St Laurent (now a Senior Policy Advisor at Environment and Climate Change Canada):

- “Exploring public acceptability of direct air capture and storage: Climate urgency, moral hazards and perceptions of the whole versus the parts of a carbon dioxide removal system,” in the journal Climatic Change; and

- “Public evaluations of four ocean-based carbon dioxide removal approaches” in Climate Policy.

In their analyses of data from a representative survey of residents of B.C. and Washington state in 2021, Satterfield and Nawaz dug into perceptions of carbon removal technologies as influenced by people’s sense of climate urgency, beliefs about the marine environment and our responsibility for natural systems.

The researchers explored the relationship between these views and people’s comfort with various technologies, including Solid Carbon, which proposes offshore direct air carbon capture and storage, as well as coastal restoration and ocean fertilization (adding nutrients like iron to the ocean to increase photosynthetic activity and concomitantly remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere).

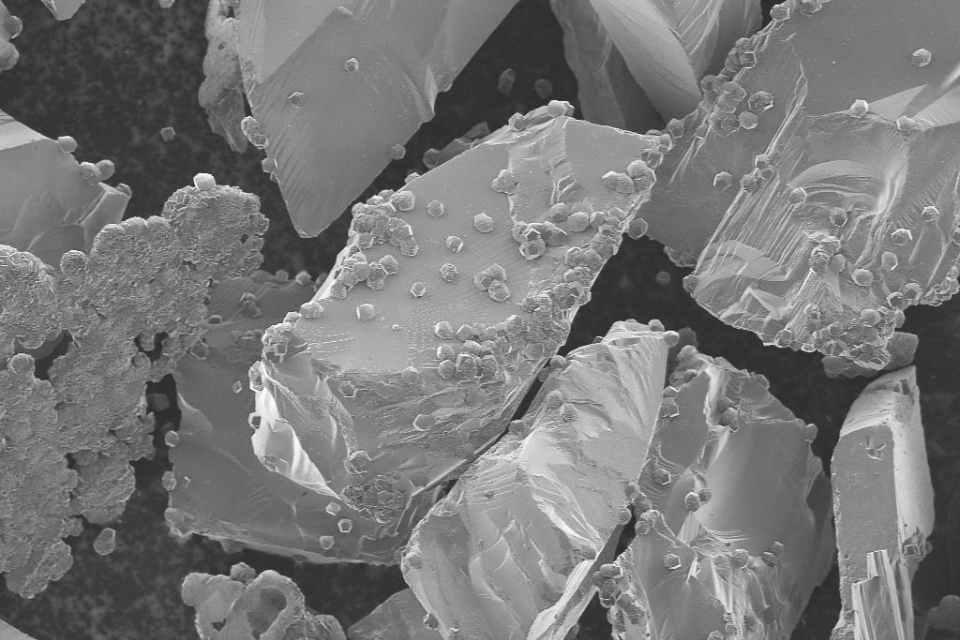

The focus of “Exploring public acceptability of direct air capture…” was Solid Carbon — which aims to draw carbon from the atmosphere and inject it into sub-sea floor basalt, where it will ‘mineralize’ or turn to solid rock over time.

Satterfield says going into the projects, “We really had no idea what kind of thinking or perceptual landscape existed for these technologies.

“Is the purpose [reduced atmospheric CO2] really key for people or is the technology itself the focus in certain ways and what kind of ways? That’s the essence of our investigation.

“How do people think about wind generation at a fairly large scale to run a system? Do they associate the injection part of Solid Carbon and the mineralization as untenable or doable, viable?”

Adds Nawaz: “We found the Solid Carbon-type system sits in the middle in terms of comfort with other technologies we studied. People tended to have more comfort with coastal restoration as compared with Solid Carbon, but they were less comfortable with technologies like ocean fertilization and ocean “alkalinity enhancement.”

Asked why it’s important to consider the public’s response to NETs if they’re shown to be technologically feasible, Satterfield says considerations include: “Who will this impact and should they not have a say in whether it’s done? What are the worst-case scenarios and the best-case scenarios? What are the relative options? What’s the total suite of possibilities here and is this the best one?

“To me, it’s not just about its technical workability,” nor is that the dominant factor in people’s views on NETs, she says.

“One of the predicting variables was sense of responsibility for natural systems,” she says. “Often, people with strong environmental views can reject these technologies but, in this case, it wasn’t quite that way.”

Satterfield adds: “Things are shifting quickly as people continue to live with extreme weather events… We’re seeing in the [academic] literature in general increased tolerance for getting on to trying new things that might not have been acceptable 10 years ago or five years ago.”

She and Nawaz will continue their research throughout early 2023 by conducting workshops on Vancouver Island with First Nations and environmental groups to explore more deeply people’s thinking about NETs.

• Read how carbon dioxide taken from the atmosphere and injected into the subsea floor off Vancouver Island may turn into solid rock in about 25 years.