by Alyssa Hill and Dylan Clark

As people across British Columbia know first-hand, affordable housing is increasingly beyond reach. With this housing crisis top of mind, governments are keen to accelerate development and make housing affordable again.

Despite those commitments, climate change is making it more challenging than ever to build safe and resilient homes. Wildfire, flood, and extreme heat risks are increasing in many regions of B.C. including across Metro Vancouver — the territories of the q́ićəý̓(Katzie), q́ʷɑ:ńƛ̓əń (Kwantlen), kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem), máthxwi (Matsqui), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), qiqéyt (Qayqayt), se’mya’me (Semiahmoo), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish), scəẃaθən məsteyəxʷ (Tsawwassen) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh).

To safely shelter people and address the large housing stock shortage, new homes will need to hold up to tomorrow’s climate hazards.

In this two-part series, we unpack what B.C.’s new housing policies could mean for the province’s climate risk. This first Explainer focuses on flood risks in areas of urban growth. The second will focus on the trade offs of densification and urban heat islands.

Densification and flood risks

Bill 47 is one of the recent housing policy changes in B.C. The legislation aims to increase housing density around transit hubs by removing common barriers to denser development (such as local building height, density, and parking restrictions). The legislation identifies 52 locations for immediate densification across B.C. — 46 of which are in Metro Vancouver. The Government of B.C. estimates the legislated change could add approximately 100,000 new housing units over 10 years.

Increasing density around transit hubs is generally good climate policy. More housing near public transit can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And increasing affordability of safe housing can protect people from wildfire smoke and extreme weather.

Unfortunately, there are downsides to consider. Climate change is raising the risk of floods in some Metro Vancouver neighborhoods. There are about 32,000 buildings in a current high-risk flood zone in Metro Vancouver. Sea level rise and more extreme rain events could roughly double that number over the next 30 years — and that’s before accounting for new buildings.

Location, location, location

Floods in Metro Vancouver can happen when: 1) rivers rise beyond their banks (fluvial floods); 2) when a high tide rises above beaches and dikes (coastal floods); 3) and when storm sewers back up (pluvial floods).

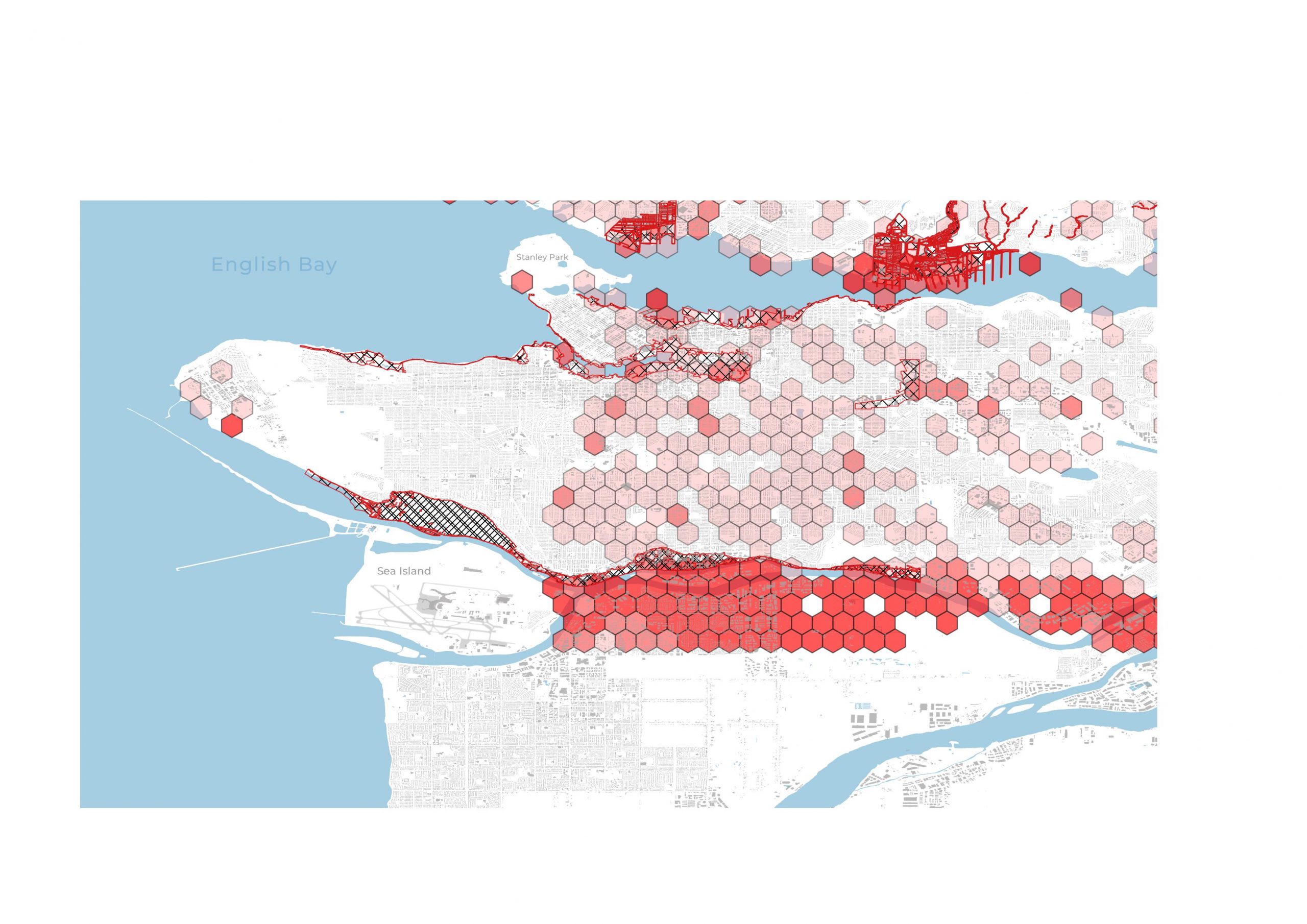

Many Metro Vancouver municipalities are exposed to all three types of floods. However, zoning and development restrictions vary across the region. Areas where new buildings need to account for flood risk are shown in red cross-hatching here.1

Municipal flood risk maps and development bylaws only focus on a few types of flood risk, leaving large gaps. Stormwater flood risk is not considered in bylaws at all in Richmond, Vancouver, or the District of North Vancouver. The City of Richmond does not have any designated flood risk zones.

For a more comprehensive look at flood risk across Metro Vancouver, we added risk data from the insurance industry and recent academic studies.

Red hexagons show flood risk across the region. The darker the red, the higher percentage of buildings at risk in that area2.

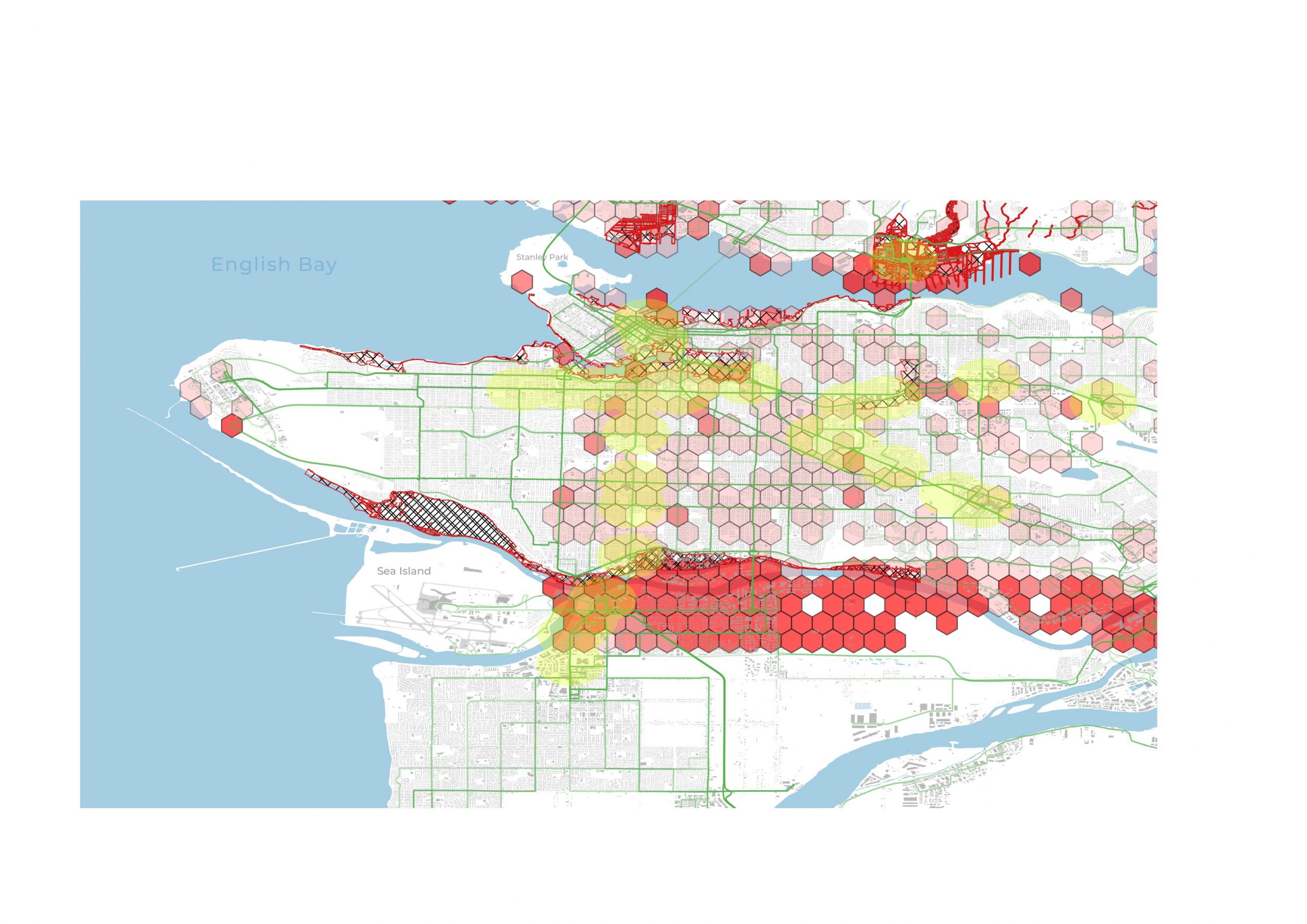

Next, to assess how B.C.’s new “transit-oriented-development” policy may affect regional flood exposure, we mapped the densification zones for Metro Vancouver, within 800 metres of Sky Train stations and 400 metres of select bus stations. We’ve marked the densification zones with yellow, main transit routes with green, and stations designated for densification by Bill 47 with green dots.

We found that some areas prioritized for housing growth (yellow) are at high risk of flooding (red hexagons).

The climate resilience assessment for the Broadway SkyTrain expansion also identified sea level rise and stormwater flooding as medium to high risk for a number of stations.

Fortunately, Bill 47 defers to local flood risk zoning bylaws. Because of that, the False Creek area of Vancouver and areas along North Vancouver streams and rivers will be less likely to densify.

But there are gaping holes in flood risk maps and bylaws. For example, the City of Richmond has not updated zoning bylaws to reflect current and future flood risk of the Fraser River. And many municipalities in Metro Vancouver do not consider stormwater flooding at all.

Better data, better decisions

Better and publicly accessible flood risk data is foundational to a common understanding of where risks exist and where new housing investments belong. Data transparency will support local policy development and private sector adaptation. Indeed, B.C.’s new flood strategy includes actions intended to increase flood risk information and further integrated approaches to manage risks.

Under the current policy regime, municipalities are largely responsible for ensuring growth in high-risk areas will stand up to climate change. And while there are data gaps, municipalities generally know where their high-risk neighbourhoods are. The critical next step is disclosing and building for those risks.

Unless flood risk is better reflected in zoning policies, there is real potential that many new homes are going to be in harm’s way. Given that B.C. will need an estimated 2.58 million new housing units by 2030 to accommodate population growth, communities cannot afford to be building in neighbourhoods that could soon be under water.

Alyssa Hill is a research lead with the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions.

Dylan Clark is the associate director of research and operations with the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions.

References

1. Data on areas with flood-related zoning restrictions is from the District of North Vancouver, and the City of Vancouver. Basemap infrastructure data is from GeoBC and Bing.

2. Flood risk is based on 200-year return periods. We defined flood risk based on Digital Elevation Maps, the Fraser Basin Council, and analysis by the Canadian Climate Institute.