By Richard Dal Monte

Every technological breakthrough carries potential and risk. In the case of the promising Solid Carbon negative emissions technology project, however, researchers have found one risk to be very low to the point of non-existent.

The project will almost certainly not cause seismic activity such as earthquakes.

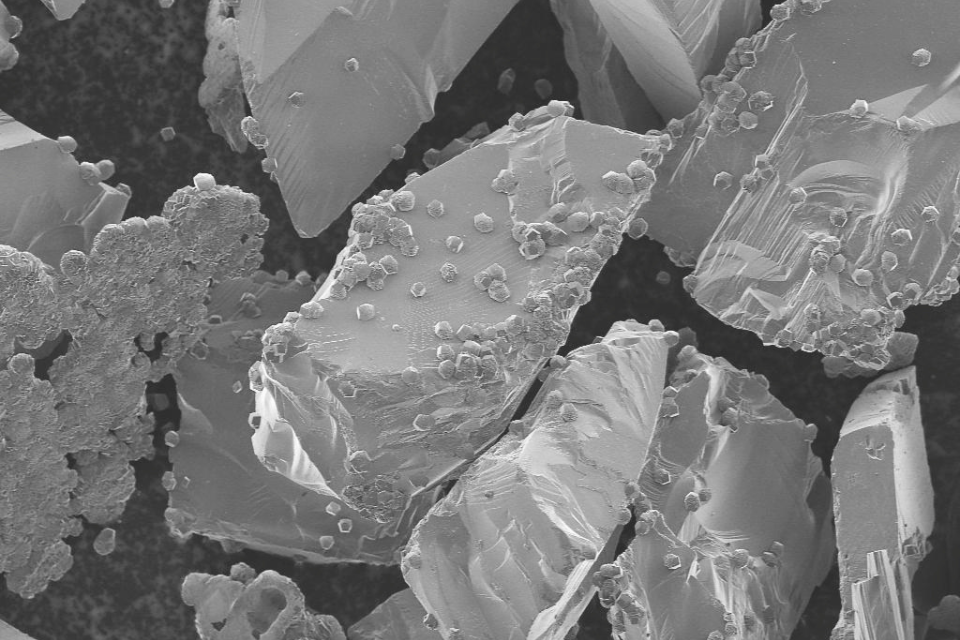

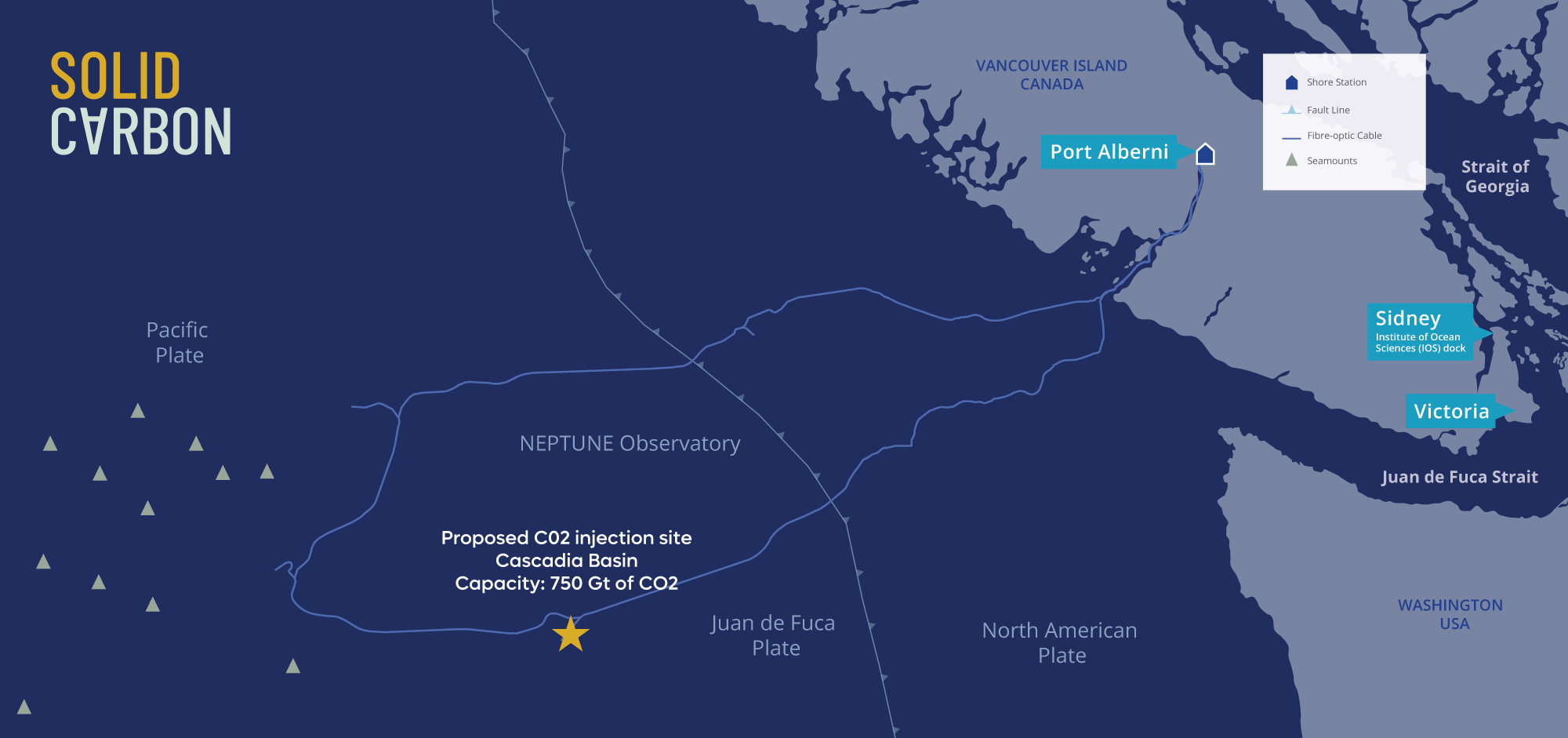

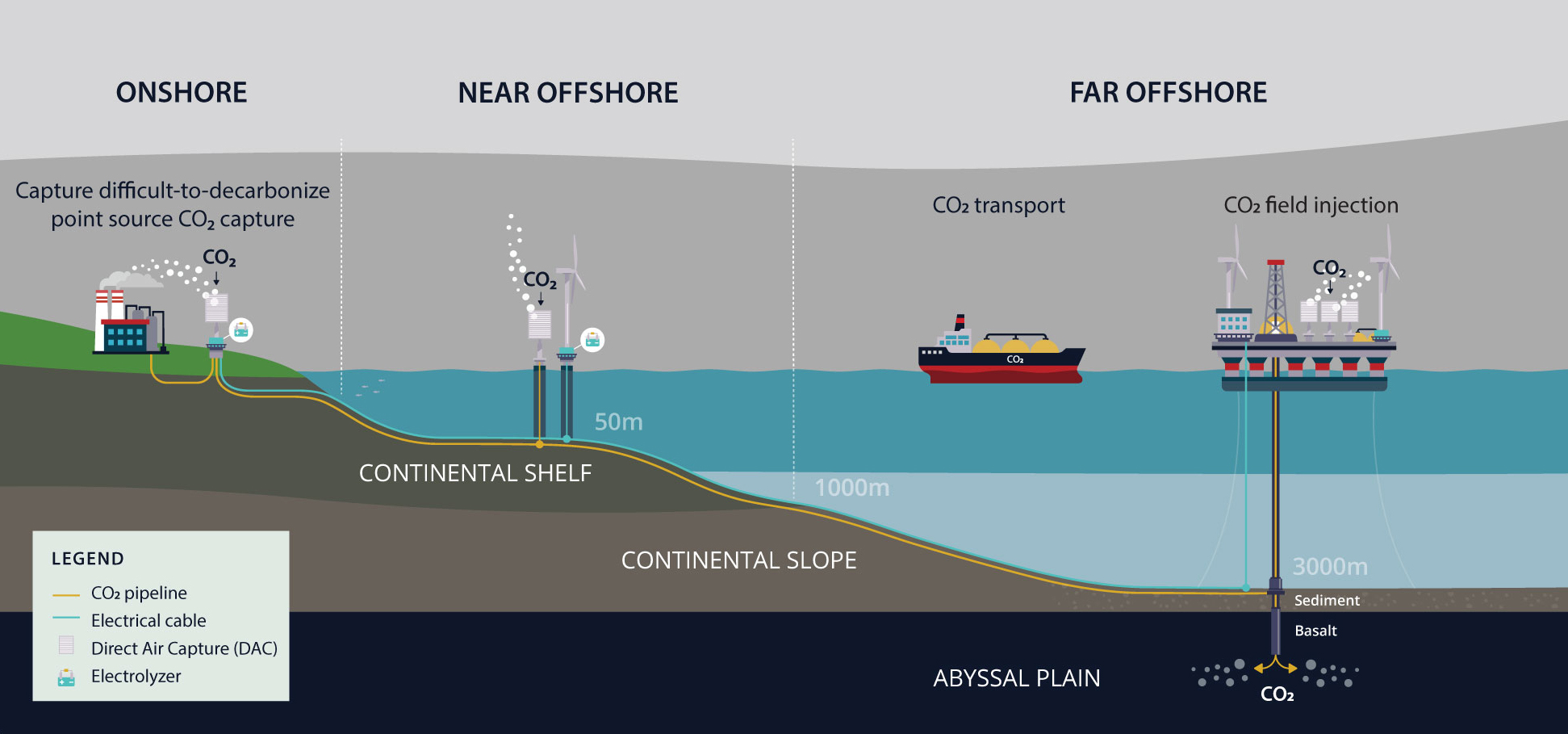

Solid Carbon, an international research team led by Ocean Networks Canada (ONC), a University of Victoria initiative, and funded by a PICS Theme Partnership grant, is investigating how to permanently and safely store carbon dioxide (CO2) in the ocean floor. The goal is to capture CO2 from the atmosphere and inject it into porous basalt rock, such as that found under the Cascadia Basin off the West Coast of Canada and the United States, where it would interact with minerals, transforming into carbonate rock.

Read more about how CO2 can turn into rock in 25 years.

Ensuring the project is seismically safe is a priority for the Solid Carbon team. Extensive computer modelling was used to examine whether injecting CO2 into the basin’s basalt could trigger seismic activity, such as slips on the faults in the Cascadia Basin. Such slips can cause local earthquakes.

In a recent article in the international journal GeoHazards titled Fault Slip Tendency Analysis for a Deep-Sea Basalt CO2 Injection in the Cascadia Basin, geophysicist Dr. Eneanwan Ekpo Johnson and a research team from the project conclude fault-slip potential from carbon sequestration is less one per cent.

This extremely low risk, they write, holds for a constant injection of up to about 2.5 megatons of CO2 per year over 10 years.

“When we talk about the site characterization, we’re basically saying the injection wouldn’t cause these faults to slip and therefore won’t cause seismic waves,” says Ekpo Johnson, who led the study as part of her post-doctoral work at ONC and the University of Victoria School of Earth and Ocean Sciences (SEOS), and now works for Natural Resources Canada (NRCan).

She says the research team, which included senior scientists from ONC, SEOS, and NRCan, studied the geology of and available data on the Cascadia Basin, including location and orientation of faults as well as stresses in the area. The team then conducted sophisticated “fault-slip” computer modelling to determine the effects of carbon sequestration.

That modelling found the faults in the area would not break, and that the risk of seismic activity from injecting CO2 is minimal.

The team determined that low risk is because the basalt rock has a great deal of pore space available to take up the CO2 and is permeable enough to spread the injected carbon around.

The findings are critical for support of continued Solid Carbon testing, says Dr. Martin Scherwath, a senior staff scientist with ONC who specializes in seabed dynamics and geological carbon storage.

“The question about the risk of pumping CO2 into the ocean crust is important and comes up almost every time this work is presented to the public,” he says. “People on the West Coast live in an earthquake zone and have concerns when they hear that the CO2 will be injected under pressure into an area where there are natural earthquakes due to tectonic stresses.”

Ekpo Johnson and Scherwath say the next step in this research is to install monitoring instruments above and below the seafloor, connected to ONC’s existing sea deep observatory at Cascadia, in preparation for when Solid Carbon eventually builds its test sites offshore.

Carbon sequestration and other negative emissions technologies are crucial for meeting climate change goals in British Columbia, Canada, and globally.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has called not only for drastic reductions in CO2 emissions to limit global warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels but also the use of negative emissions technologies such as those being studied by Solid Carbon to draw down carbon already in the atmosphere.

You can read more about negative emissions technologies in the PICS Report Survive and Thrive: Why BC needs a CO2 removal strategy now