Climate change is no longer a priority for people in B.C. Why? And can the trend be reversed?

by Samuel Lloyd and Ekaterina Rhodes

Long regarded as climate leaders, British Columbians may be faltering in their climate ambitions. Despite increasing climate disasters, climate change ranks as a voting priority for only four per cent of British Columbians, behind housing, health care, and economic concerns.

Our recent report, Promoting Climate Engagement in B.C.: Reactive and Proactive Strategies, identifies the key causes of climate disengagement in British Columbia and suggests reactive and proactive strategies to address the situation. It also highlights future research priorities and opportunities to collaborate with key stakeholders across Canada.

Causes of climate disengagement in B.C.

1. The Climate Change Counter Movement

The Climate Change Counter Movement is one of the main drivers of climate disengagement in B.C. and beyond. This movement involves various actors, including fossil fuel companies, conservative foundations, think tanks, front groups, and fake grassroots organizations, all united in protecting the fossil fuel industry from the effects of climate policy. This movement is widely active within B.C.

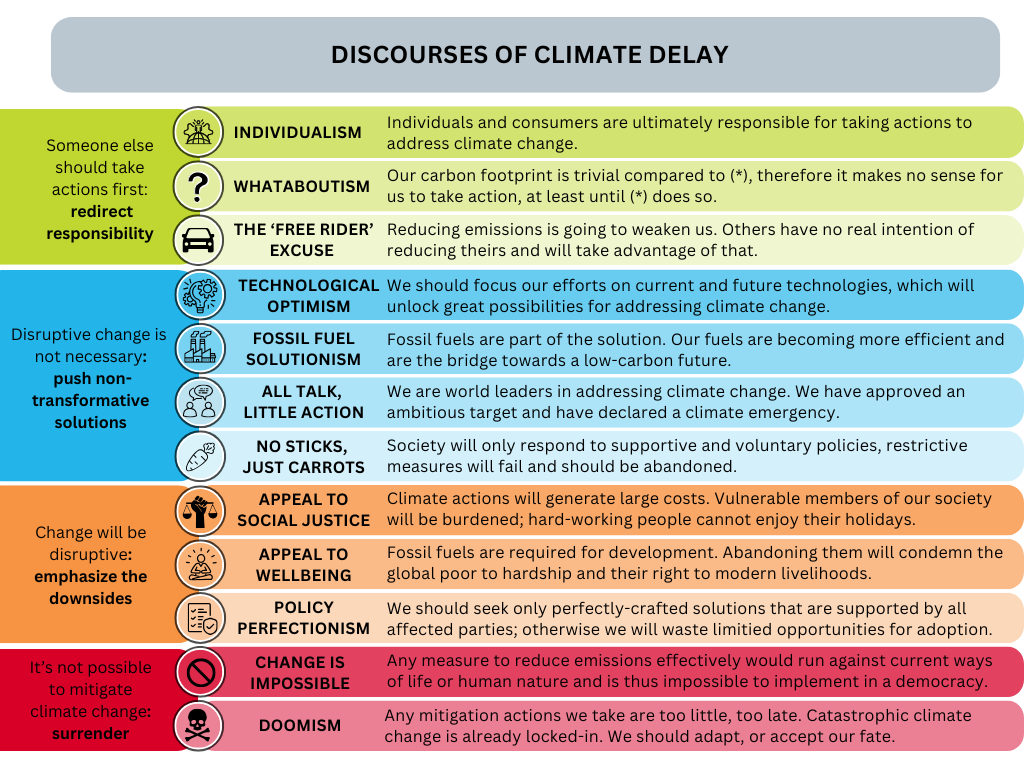

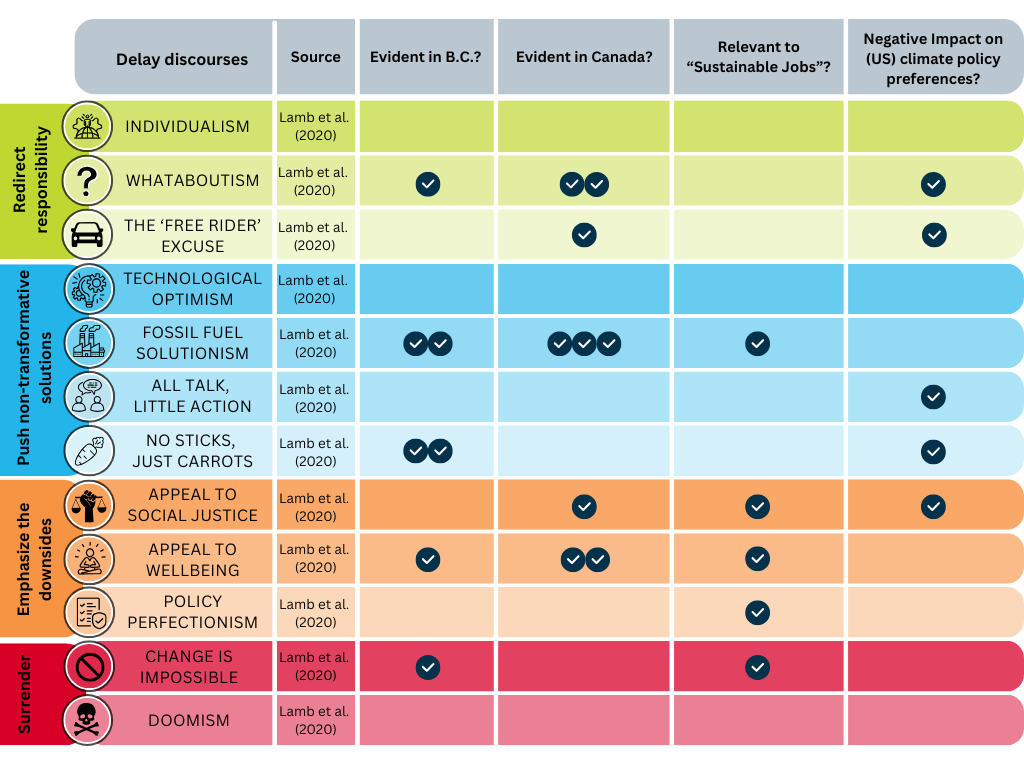

The Climate Change Counter Movement has historically used strategies such as denying the reality or human causation of climate change, voicing skepticism of its impacts, and attacking the scientists who study it. While these strategies are still relatively common in right-wing media, they are gradually being replaced by newer, more advanced tactics known as “climate delay discourses” (Figure 1).

according to whether they “redirect responsibility” for climate action, “push non-transformative solutions” to the climate crisis,

“emphasize the downsides” of climate policy, or push the public to “surrender” to climate change.

Climate delay discourses aim to slow climate action by exploiting legitimate policy discussions about which actions to take, who bears responsibility, and who should pay the costs of and receive benefits from actions to combat climate change. Some B.C. organizations, like Resource Works, aim to reduce climate engagement by arguing a transition away from fossil fuels is hopeless, and a goal that will not be achieved “any time soon, probably not in our lifetimes” (an example of a discourse best described as “change is impossible”).

The B.C. Climate Change Counter Movement also frequently uses “fossil fuel solutionism” to claim that fossil fuels are becoming cleaner and more efficient, and that the fossil fuel industry is thus a necessary part of the solution to climate change. This discourse is often paired with another known as “whataboutism”, where organizations, such as the Business Council of British Columbia, falsely claim that the fossil fuels produced in Canada are less carbon-heavy than those produced in the rest of the world, and that fast-tracking the oil and gas industry in Canada will therefore reduce global emissions.

2. Policy Design

Unpopular climate policies may also contribute to climate disengagement in B.C. While regulatory climate policies, such as the Low Carbon Fuel Standard, tend to receive broad public support, the carbon tax has proven deeply unpopular. This is likely because the cost of the tax is highly visible, while the gains are harder to see. This makes it a target for public frustration and negative media coverage, which can create backlash and undermine support for and the success of broad climate policies, as seen in the 2024 provincial election.

Solutions to climate disengagement in B.C.

In our report, we propose four strategies to address this problem:

- focus on climate policies with high passive support

- improve communication strategies to increase support for effective and potentially unpopular policies

- engage the public through climate assemblies

- hold the Climate Change Counter Movement legally, financially and publicly responsible for their actions

Shifting political priorities in B.C., Canada, and other Western jurisdictions are disrupting climate policies, but they need not alter climate ambitions. B.C. could still reduce emissions in the ‘background’, at least in the short term. This might mean the focus shifts to climate policies that receive high ‘passive’ support, such as flexible regulations and subsidy-like programs. These policies tend to face little opposition because they aren’t highly visible but are widely supported once explained. To ensure the success of these ‘passively’ supported policies, it may require avoiding policies—like carbon taxes— that risk fueling resistance to climate action.

This approach aligns with the B.C. government’s current pledge to remove the consumer carbon tax (should the federal backstop be lifted), and could be informed by research on public support for current and proposed climate policies in B.C. While this strategy reduces the risk of backlash against climate policy, effectively addressing climate change will undoubtedly require strengthening existing regulations, and introducing new mandatory policies—some of which may not always be widely popular.

To build support for stronger climate policies, effective communication strategies are key. One approach, known as “message framing”, aims to reframe climate issues to align with people’s existing values and concerns. This helps make complex climate policy feel more understandable, relevant, and personally important to the intended audience.

In B.C., emphasising the economic and public health benefits of a climate policy (without directly mentioning climate change) is likely to be an effective strategy,1 as these issues resonate strongly with voters. Other promising frames include emphasizing climate change’s inevitable impact on plants and animals; leveraging perceived peer pressure; and emphasizing how climate action can help prevent costly extreme weather events in the future. These message frames will be most effective if targeted to specific audiences, such as those of Re.Climate’s “Five Canadas”.

Another way to boost public climate engagement is through climate assemblies, which bring together a representative sample of the population, through a lottery, to study, deliberate, and make recommendations about climate-related topics. Because participants are recruited through a lottery, climate assemblies are unlikely to represent political interests, including those of the Climate Change Counter Movement. This allows assemblies to be more impartial, and to adopt a long-term perspective that takes future generations into account. Climate assemblies also promote positive and hopeful responses to climate action, increase public trust in government, and help reduce polarization around climate action. Perhaps most importantly, research suggests that people are more inclined to accept policies they may not favor if those policies were informed by climate assemblies. Intriguingly, climate assemblies are also expected to help combat the Climate Change Counter Movement by reducing the impact of climate delay discourses, although this connection requires more research.

One final strategy to protect B.C. climate engagement is to publicly map the actions of the Climate Change Counter Movement within the province. This would allow the government to hold fossil fuel companies legally accountable for intentionally spreading harmful misinformation; expose when and how the political process is being manipulated and make this clear to the public; and increase transparency about how fossil fuel funds are allocated, including who receives those funds and how they are used.

Despite shifting political priorities across North America, the B.C. government has opportunities to continue to drive meaningful action on climate. This requires both proactive and reactive strategies to counter climate disengagement in the province and to align climate policies with the core values and priority issues of British Columbians.

1 Although recent research conducted in B.C. suggests that “economic benefits” frames have the potential to backfire, and could actively reduce public support for climate policy if used without caution.

Samuel Lloyd is a PhD student in the Department of Psychology, working under the supervision of Dr. Katya Rhodes.

Dr. Katya Rhodes is an associate professor in the School of Public Administration, an associate member in the Department of Psychology, and a member of the Institute for Integrated Energy Systems at the University of Victoria.